User guide

Finding your way around the guide

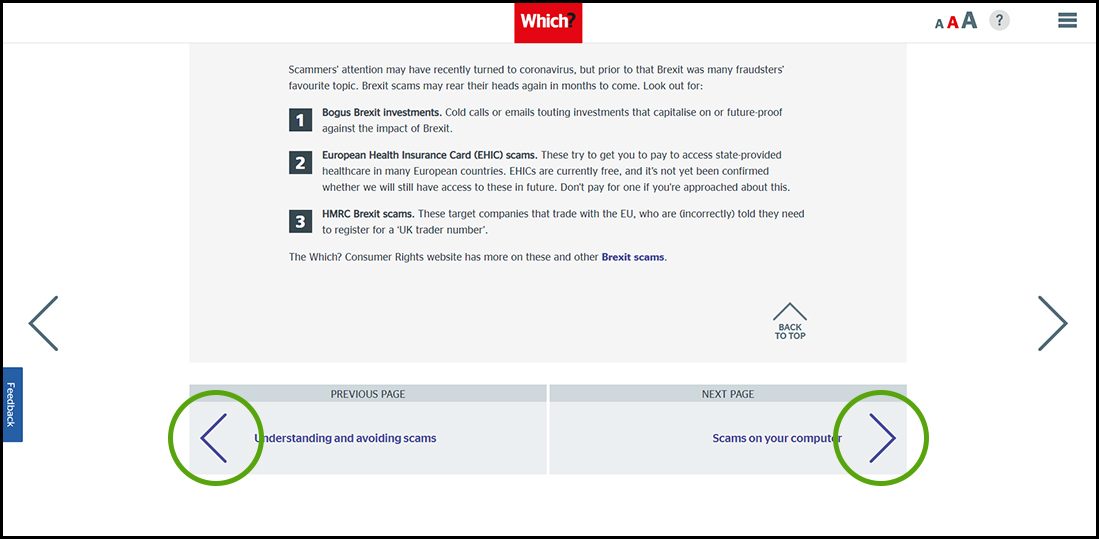

To navigate between pages, click or tap the arrows to go forwards to the next page or backwards to the previous one. The arrows can be found either side of the page and at the bottom, too (circled in green, below).

Menu/table of contents

Click or tap on the three horizontal lines in the top-right of your screen to open the main menu/table of contents. This icon is always visible whether you're using a computer, tablet or smartphone. The menu will open on top of the page you’re on. Click on any section title to visit that section. Click the cross at any time to close the table of contents.

Text size

On a computer, you'll see three different sized letter 'A's in the top-right of your screen. On a smartphone or tablet these are visible when you open the menu (see above). If you’re having trouble reading the guide, click or tap on each of the different 'A's to change the size of the text to suit you.

Pictures

On some images you'll see a blue double-ended arrow icon. Clicking or tapping on this will expand the picture so you can see more detail. Click or tap on the blue cross to close the expanded image.

Where we think a group of images will be most useful to you, we've grouped them together in an image gallery. Simply use the blue left and right arrows to scroll through the carousel of pictures.

Links

If you see a word or phrase that's bold and dark blue, you can click or tap on it to find out more. The relevant website will open in a new tab.

Jargon

If you see a word or phrase underlined, click or tap on the word and small window will pop up with a short explanation. Close this pop-up by clicking or tapping the cross in the corner.

Help

On a computer, you'll see a question mark icon in the top-right of your screen. On a smartphone or tablet this is visible when you open the menu (see above).

Clicking or tapping on the question mark will open this user guide. It opens on top of the page you're on and you can close it any time by clicking or tapping the cross in the top-right corner.

The cost of care

Care is expensive and the bills can mount up. Knowing how much you’ll pay for care and how costs might change will make things less stressful all round.

Care at home: what will it cost?

In January 2019, the UK Homecare Association suggested a minimum charge of £18.93 per hour for domiciliary care. Domiciliary careCare provided to someone in their own home. But exact amounts will vary, depending on where your relative lives in the UK. And costs will be significantly affected by the level of care needed.

Live-in home care is becoming an increasingly popular choice. There are two models:

- Introductory care service: where carers are introduced by an agency. Carers are self-employed and responsible for paying their own tax and National Insurance, and are paid directly by their clients. Care fees typically start at around £650 per week, but can be substantially higher.

- Fully managed service: where the company or agency providing the care employs and supplies its carers directly. Typical costs for this service are £800 to £1,250 per week, but could be as high as £1,600 for individuals with more complex care needs.

Care homes: costs and concerns

In 2017–18, the average weekly cost of a room in a residential care home in the UK was £622, and a room in a nursing home cost £856. However, these are only averages. The bill could be considerably higher, depending on where you live.

Someone who is paying their own fees will quickly start amassing a sizeable bill, especially as the average figures quoted here include fees for rooms that are funded by local authorities, who consistently pay less to care homes than self-funders do. Serious medical conditions, including dementia, could also mean even higher costs.

If your relative lives in Lancashire and moves into a residential care home, the likely cost will be around £31,000 in fees each year. If they live in Kent, the annual fees for the equivalent level of care are likely to be closer to £40,000.

Who covers the costs?

There are three ways in which care is paid for in the UK: the person being cared for (or their family) pays all the costs for their care, known as self-funding; the local authority funds some or all of the care; or, in some cases, the NHS contributes to some or all of the care.

Do you qualify for funding?

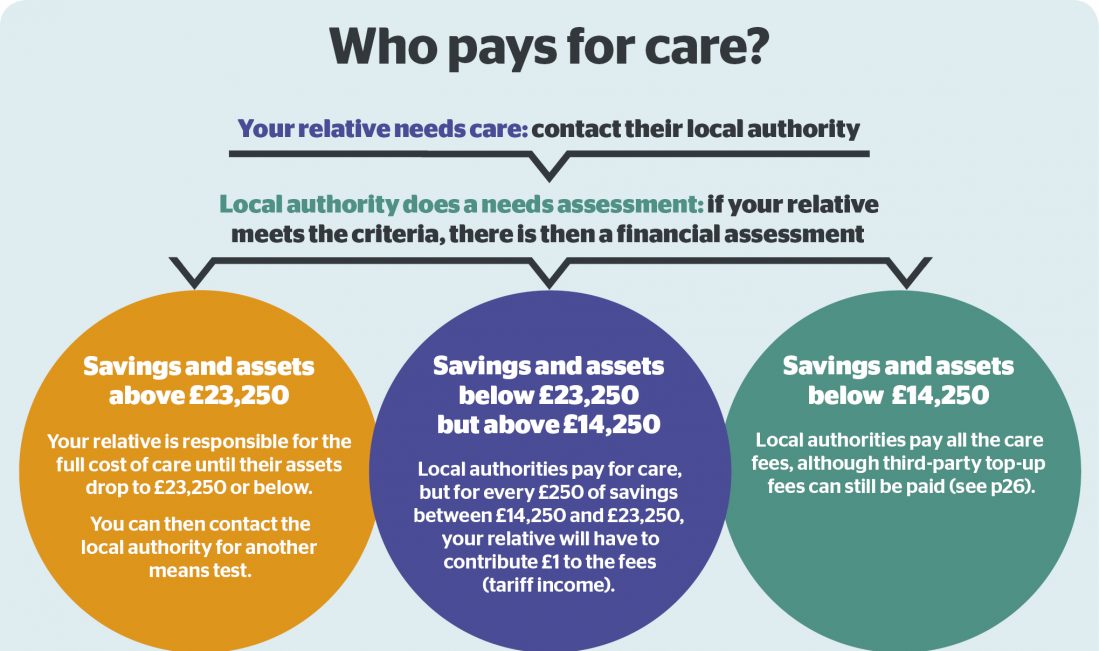

To decide if a person is eligible for financial support for care, the local authority will first carry out a needs assessment (see the section Care in the home).

If your relative is assessed as having ‘eligible needs’, the council will then offer to carry out a financial assessment – a means test used to determine how much money, if any, they will pay towards care to meet those needs.

How the financial assessment works

Although a financial assessment isn’t mandatory, it is worth having one done if your relative is considered to have eligible needs. The rules are quite complex and there are variations depending on whether the assessment is for care at home or in a care home.

The assessment looks at capital (assets and savings) and income – see the diagram below for more details on the rules that apply in England and Northern Ireland. In Scotland, personal care at home is free to those over 65 who have been assessed as needing it; for care homes, the capital limits are £17,500 and £28,000. In Wales, the threshold above which people pay their fees is £50,000 for residential care (i.e. care homes), but £24,000 for non-residential care (i.e. domiciliary care). The amount paid to care providers varies from authority to authority; it also varies depending on the level of care needed.

If your relative is being assessed for a move to a care home and they own their own home, its value will be part of the means test – unless a spouse, partner or relative aged over 60 is living there. If the financial assessment is for care at home, the value of the main home will not be taken into account.

The financial assessment will also consider any income, investments, pensions and benefits, savings, and stocks and shares. Some income, including certain pensions and benefits, may be excluded. It also excludes certain capital assets, such as personal possessions, the surrender value of life insurance policies and annuities, investment bonds with a life insurance element and some payments that are received from trusts.

YES If your relative is moving into a care home, the value of their own home will be counted as capital.

NO If a spouse, partner or relative aged over 60 will stay living in the house after someone moves into a care home, the value of the house will not be counted.

NO If your relative is being assessed for care in their own home, the value of their home is not counted as part of their capital.

Personal expenses

Everyone is entitled to a personal expenses allowance (PEA) to cover the cost of personal items, such as toiletries and haircuts. This amount is excluded from your relative’s income for the purposes of the financial assessment. As of April 2019 the PEA figures are a minimum of £24.90 per week (England and N. Ireland); £27.75 (Scotland); and a minimum of £29.50 (Wales).

Controlling your budget

In England, local authorities must offer people who qualify for funding the option of managing their own personal care budget. Your relative can then decide how the money is spent, giving them more flexibility and greater control over the services they use, rather than accepting the council’s ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach. The amount of funding is not fixed, being calculated from the needs and financial assessments. In Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland the system is slightly different and is known as ‘direct payment’.

Getting help from the NHS

The NHS can fund an individual’s care, under certain circumstances. This comes either via NHS continuing healthcare, for people with a rapidly deteriorating condition; or via NHS-funded nursing care – a contribution towards the cost of registered nursing care in a nursing home.

For 2019–20 this is £165.56 a week (England); £257 (Scotland); £149.67 (Wales); and £100 (Northern Ireland). The criteria are complex, but it’s worth asking if you think your relative may qualify. Read our articles on NHS funding for more information.

If you are helping an older person with their care plans, sooner or later you’re bound to face some complex financial questions. From capital gains tax to funding long-term care, the Which? Money Helpline can help you with your financial queries.

Third-party top-ups

Third-party top-up fees are a way of paying the difference between how much the council is willing to pay to a care home, and the actual fees that the care home charges to self-funding residents.

Residents can’t pay their own top-up fees (they shouldn’t be able to afford this if they qualified for local authority funding), so it’s normally a relative, friend or charitable organisation who might pay. There is no legal requirement for this, so payment is voluntary.

You might consider paying a top-up fee if your relative:

- would prefer to live in a care home that costs more than the council is prepared to pay, or for genuine extras, such as living in a larger room or one with a better view

- wants to live in a more expensive area to be closer to family or friends and this wasn’t identified in the needs assessment

- was self-funding but is now eligible for local authority funding and wants to stay in the same home, which isn’t contracted to the council, or the council believes your relative’s needs could be met in a lower-cost care home.

Whoever is paying the top-up fee will need to sign a written agreement with the local authority. The care home might ask for the top-up to be paid to them, but the government suggests the contract rests with the council, who will invoice the third party for their contribution to the overall fee.

If you are considering topping up your relative’s funding, be aware that, when the care home increases its fees (usually annually), the local authority may not increase its standard rate by the same amount. This means the third-party top-up could become disproportionately more expensive.

● Society of Later Life Advisers

● Which? Later Life Care – from self-funding and benefits to local authority assessments